Changing the menstruation conversation

Depleted shelf on the “Feminine Hygiene” aisle at the Brookwood Village Target (photo by Marin Poleshek).

October 13, 2022

It’s common knowledge that, because I am a woman, I have a menstrual period. However, you likely have not heard this declared openly. Why is this normal?

As many know, the world we live in today has been constructed on a patriarchal platform. For most of history, females have not received the same rights, freedoms, or recognition as males. And, despite the societal dependence on women to bring children into the world, other functions of the female body are unknown and underrepresented.

In a shocking number of communities and cultures, menstrual periods continue to be associated with uncleanliness and shame. Though not held by all, this archaic perspective creates a dialogue around menstruation that is extremely negative for women.

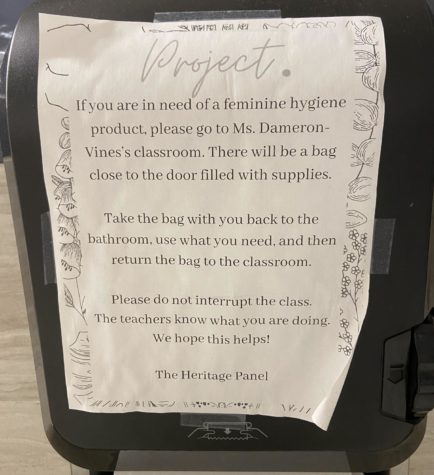

As a result of these negative beliefs, many women lack sufficient understanding of the functions of their own bodies. Because topics such as menstruation and birth control are treated as taboo in public spaces, accessing reliable information about female health can be challenging. Further contributing to the problem are schools, which are continually removing classes such as Health and Sexual Education from their required curriculums. Not only does this deprive students of learning crucial information about their bodies, but it also inhibits young women from having a space to start conversations about female well-being.

But what does this have to do with the Homewood community?

In a poll of around 300 HHS students, only about half reported feeling comfortable discussing menstruation while at school. Adding to this issue are global economic crises that are actively afflicting the Homewood community.

In recent years, the prices of period products have risen significantly. While a portion of this increase is due to pandemic-rooted supply chain disruptions, the root of this problem is something much deeper: pink taxes.

Though pink taxes are not actual taxes imposed on feminine hygiene products, the term refers to the elevated prices that women pay for products used by all genders. These items are hygiene necessities such as deodorant, shampoo, and razors- things that are non-negotiable for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. In reflection of the package designs for these products, this disparity has received the nickname “pink taxes.”

In some cases, the prices of these products prevent individuals from being able to afford them. As aforementioned, these items are not optional for the majority of families, and the lack of affordability renders many unable to take care of themselves properly.

Further complicating this is a recent shortage of period products in stores such as Walmart, Target, and Publix. Though companies that produce period products have not exactly lost business, lack of raw materials and labor availability have stripped store shelves of much of their stock. Because period products are tailored to the needs of different women, this shortage has left some women scrambling to find the specific products they need.

But what can we do? How can we help alleviate the effects of this global crisis?

In my opinion, the most effective way is to simply start conversations, especially in schools. For many, the topic of menstruation is taboo and does not receive the attention necessary to change the narrative.

If you feel called to do more, contact your local and national authorities to support laws that help women. If you think this request seems lofty, look to the others that are taking action:

Scotland has recently passed a law making period products completely free and available in public places such as bathrooms, libraries, and schools.

The city of Madrid is currently working to allow women to take three to five days off work each month to administer their menstrual periods.

Above all, the most important tool to empower females is knowledge. Without a fundamental understanding of their bodies, women do not have the necessary resources to advocate for themselves politically, socially, or psychologically.

Change is possible- we simply need to see and pursue it.